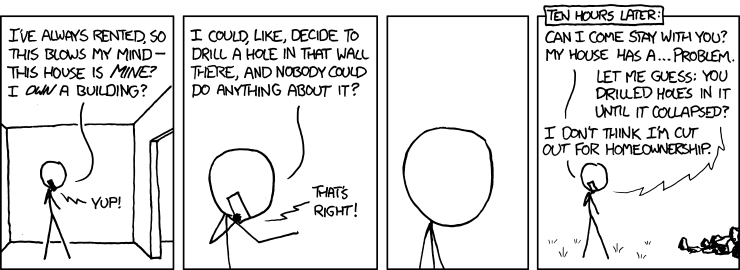

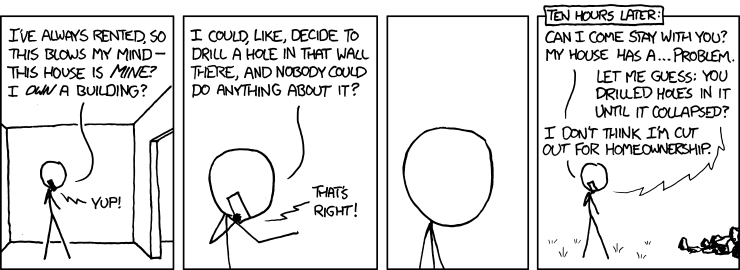

Once you’ve bought a house there is a temptation to be very Munroevian about the whole matter:

The Munroevian approach to homeownership. (Source: xkcd.com/905/)

It’s been pretty fun geeking out about home maintenance options, making plans for repairs and additions, and even picking up a hammer myself now and then. There are several surprisingly informative websites with details about how houses work, including:

- Inspectapedia: for example, this article about the insulation we just had installed.

- Check This House: for example, this article about the importance of second-floor air return ducting (a potential long-term maintenance item for our house).

Six months after closing I understand a little better the #1 question in buying a house—“how much house can I afford?”—or, more to the point, “how big a monthly housing expense can I afford?”

Monthly housing expense = mortgage payment + homeowners insurance + property tax – interest tax deduction + maintenance [or association fees]

Mortgage payment:

Conventional wisdom says to make your mortgage payment as large as possible. It will be painful now but less painful over time, especially as your earnings rise over the course of your career. That easing is because your payment will stay the same over the lifetime of your mortgage: If you have a 30-year mortgage and you make $1000/month payments today (on principal and interest), you’ll still be making exactly $1000/month payments in 29 years.

The effects of inflation will mean that, in 30 years, your $1000/month payment will only feel like a $400/month payment. (Note however that it is statistically unlikely that you will hold the same mortgage for 30 years—I’ve read several times that mortgages average about 7 years before the house is sold or refinanced.)

Low interest rates are good except for one thing: I worry about resale value if interest rates rise significantly. At 3.5% interest rates, a buyer who can afford $1000/month payments can buy a $225,000 house. But at 7.0% rates, that same buyer can only buy a $150,000 house.

When interest rates go up, many prospective buyers won’t be able to afford to pay as much for your house as you did. Will we have problems selling our house without taking a bath?

Homeowners insurance:

We pay $90/month. Annoyingly, our loan documents require a $1,000 deductible for the policy—i.e., we’re not allowed to crank up the deductible to lower our rate.

One thing that surprised me is that none of the “big boys” (Allstate, State Farm, GEICO, etc.) write insurance policies in Massachusetts. I had a similar problem trying to get renter’s insurance in Florida. Perhaps we should move to some milquetoast state with uniform laws and no propensity for natural disasters?

Property taxes:

You can find out what we (or your neighbors, or pretty much anybody) pay for property taxes by looking them up on the county tax assessor’s website; these are matters of public record.

As with many jurisdictions, Boston has a residential tax exemption—your taxes are reduced by $130/month if the property serves as your principal residence. So budget for additional expense if you plan to rent out your house.

Tax deduction:

I can’t imagine the federal mortgage interest tax deduction surviving much longer. My guess is that it will be phased out over the next few years. Without the deduction our monthly housing expense will increase by $300/month.

Also, as with rising interest rates, I suspect a tax deduction phase-out will have a depressing effect on home resale prices.

Maintenance:

The expensivity of home maintenance has surprised me. So far we’ve spent money in three categories:

A. Required maintenance: $10,000 for new roof shingles.

The home inspectors and roofing experts who evaluated the house initially gave us a one to two year window for replacing the roof. However, when we had roofers up to do minor repairs (repointing the chimney, recementing the vents, cleaning the gutters) they found cracking asphalt and other problems that prompted us to schedule the replacement immediately. The new roof will hopefully be good for about 20 years.

B. Opportunity-cost improvements: $3,600 for whole-house insulation and $3,900 for an oil-to-gas conversion of the furnace.

Massachusetts has an astounding program called Mass Save where you can receive an interest-free loan to defray the up-front costs of energy-efficiency improvements to your house. The improvements will pay for themselves within three years (in the form of reduced utility bills), plus the house is more comfortable afterwards. It’s a total win-win-win program for homeowners.

There are also incentive rebate programs for efficiency improvements. The insulation work actually cost $5,600 (minus a $2,000 rebate from Mass Save); the furnace conversion cost $4,700 (minus a $800 rebate from our gas utility company).

We could have waited a year to make these improvements—the oil heater and indoor fuel oil tank were only about ten years old—but with the rebates and interest-free loan there was no reason not to jump on these, especially with the possibility that the program might not be renewed in future years.

The old 275-gallon oil tank, taking up space in our basement.

With the oil tank removed, there is space aplenty to eventually install a demand water heater.

C. Functional improvements: $6,000 for electrical work and exhaust ventilation.

Our house is over 100 years old and (not surprisingly) didn’t have outlets or lights or exhaust fans everywhere we wanted them. Worse, we were occasionally tripping breakers by running too many appliances on a single circuit.

We could have waited a year or two before performing this work, but I wanted to have the new wires pulled before having the insulation work done on the exterior walls and in the attic. (The electricians said they could certainly do it even after the insulation was put in but that it would be “messier”.)

Also, it is a perpetual source of happiness for me to walk into the kitchen and see:

New externally-vented range hood. We use it daily. The white square of paint is where the over-the-range microwave used to be hung.

or into the bathroom and see:

New bathroom electrical outlet (one of two). Previously the bidet power cord ran along the bathroom floor, via an ugly grey extension cord, into the outlet by the sink.

Every time I take a shower I look over at the safer, neater, convenient bathroom outlet and feel the joy of homeownership. (We also solved four other extension-cord problems elsewhere in the house, each of which bring joy in turn.)

D. Deferred maintenance and improvements: Water heater replacement, carpentry, repointing the basement walls.

Our water heater is nine years old and has a nine year warranty. I don’t believe it’s been cleaned nor flushed regularly, nor had the sacrificial anode replaced, so given the lack of maintenance I worry that it could start leaking—that would be a big problem since there is no floor drain in the basement—so I plan to replace it in 2013 with a demand water heater.

Demand water heaters need a fat gas pipe. They consume up to 200,000 BTUs/hour or more; in comparison, our new high-efficiency furnace that consumes only up to 60,000 BTUs/hour and a typical gas stove and oven consume up to 65,000 BTUs/hour. Our current gas pipe is thin, old, and lined (basically not up to snuff) so I’ve submitted an application to the gas company to lay a larger pipe in the spring. I’ve requested a future-proofed pipe large enough to accommodate those three appliances plus a potential upgrade to a gas clothes dryer and a natural gas grill.

The lesson learned for me is if you’re buying a house, keep at least an extra $10,000 in reserve to cover any urgent maintenance items. In other words, don’t completely exhaust your financial reserves by making a larger-than-needed down payment or purchasing new furniture too quickly.

In aviation there is a concept of prepaying into a maintenance fund every time you fly your own aircraft. You know that you’re required to pay for major maintenance every 2,000 flight hours—at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars—so you divide that cost by 2,000 and prepay $10 into your maintenance fund for every hour you fly.

I’ve seen similar recommendations about prepaying for home maintenance. You know that you’ll periodically have to pay for roofing work, new water heaters, and whatnot, so forecast out when you’ll make those repairs and start prepaying into a maintenance fund. (If you buy into a condo association, part of your condo association fees are earmarked for exactly this purpose.)

There are a couple other housing-related websites I’ve been reading regularly, including The Mortgage Professor and (perhaps of local interest only) the Massachusetts Real Estate Law Blog. The professor relates a story of an ill-prepared homeowner, who asked:

“I hadn’t been in my house 3 weeks when the hot water heater stopped working. Only then did I realize that I hadn’t been given the name of the superintendent…who do I see to get it fixed?”

One of the challenges we’ve faced is finding good contractors. Here’s what I’ve learned about finding good contractors:

- Get three quotes. Not because you’re trying to find the absolute lowest cost, but rather that you’ll hear three different perspectives on what they think you should do. For example, I had three heating contractors in to discuss the oil-to-gas conversion. One suggested that I simply replace the burner on my existing furnace; one suggested that I install a new 100,000-BTU gas furnace; one suggested that I install a new 60,000-BTU gas furnace because of the square footage of the house. Those three conflicting opinions gave me a lot of information to mull over; in the end I chose option #3 and it’s worked out perfectly.

- Ask your neighbors for recommendations. Several folks in my community recommended a particular roofing company; I ended up hiring them and was thoroughly satisfied with their work and professionalism.

- Join Angie’s List for recommendations. I hesitated to join at first—whining about how it costs money!—but in the end I figured was only hurting myself by not joining. I ended up hiring an electrical contractor that I found on Angie’s List and was thoroughly satisfied with their work and professionalism.

And here’s what I’ve learned about hiring contractors:

- Read the installation manuals yourself. I wasn’t happy about how the heating contractor didn’t bother to configure the DIP switches on my new furnace. (Specifically, he didn’t set the furnace’s fan speed to match the tonnage of the air conditioner’s compressor; he claimed it wasn’t important because he’d never done it before.) So, I read up on furnace fan speeds and compressors myself, make the correct setting myself, and now find myself self-satisfied with better air conditioning performance.

- Do your own homework before the contractors arrive. I asked potential electricians about adding an exhaust fan in our half-bathroom. One of them suggested that I buy the fan and he’d install it. I asked why; he explained that if it were up to him he’d just buy the cheapest fan available, but he felt I’d likely be interested in a higher-end fan. And he was correct! After I scoured the Internet for information on exhaust fans I identified one of the low-sone (quiet) fans as the one I wanted, and we’re much happier with this choice than we would have with a louder fan. (Note: I also installed a wall-switch timer on the exhaust fan—a great idea that I learned about while doing my homework on options for fans.)

- Keep track of your paid invoices. Some work you perform might increase your basis in the property (see IRS Publication 523), which could reduce the amount of tax you (might) pay when you sell the house.

- Be ready to be flexible. The heating contractor said it’d be done in one weekend, but it ended up taking a month and a half before the last of the work (sealing the old hole in our chimney) was complete. The roofing contractor gave a two-week window in which they’d do the work, then ended up doing the work three days before the start of the window. The insulation contractors said it’d be a two day job, but it ended up being a three-day job spread out over two weeks. Fortunately, all of our contractors have taken pride in their work—so we’ve been left largely happy with the work that’s been done.