The weather cooperated (somewhat) and I indeed got to fly last weekend for my second solo cross-country flight:

By the end of the flight I was positively giddy; as I walked back to my car I texted Evelyn the above picture with the caption “I LOVE FLYING”. Almost all of my flight training has left me grinning from ear-to-ear, but this flight was by far the most fun I’ve had yet.

(Almost all of my flight training has left me grinning: The required night landings weren’t nearly as much fun as I thought they would be, especially since my instructor chose to test my performance under pressure — asking me to fly an unfamiliar approach to the runway, while simulating a landing light failure, all during a rushed and chaotic situation — and I didn’t handle it particularly gracefully. But “trial by fire” was the whole point, and I feel that I learned from the experience and am better prepared to execute emergency landings at night. I also did manage to land the airplane despite the chaos, though I’d drifted off the runway centerline and was still drifting as the wheels touched down.)

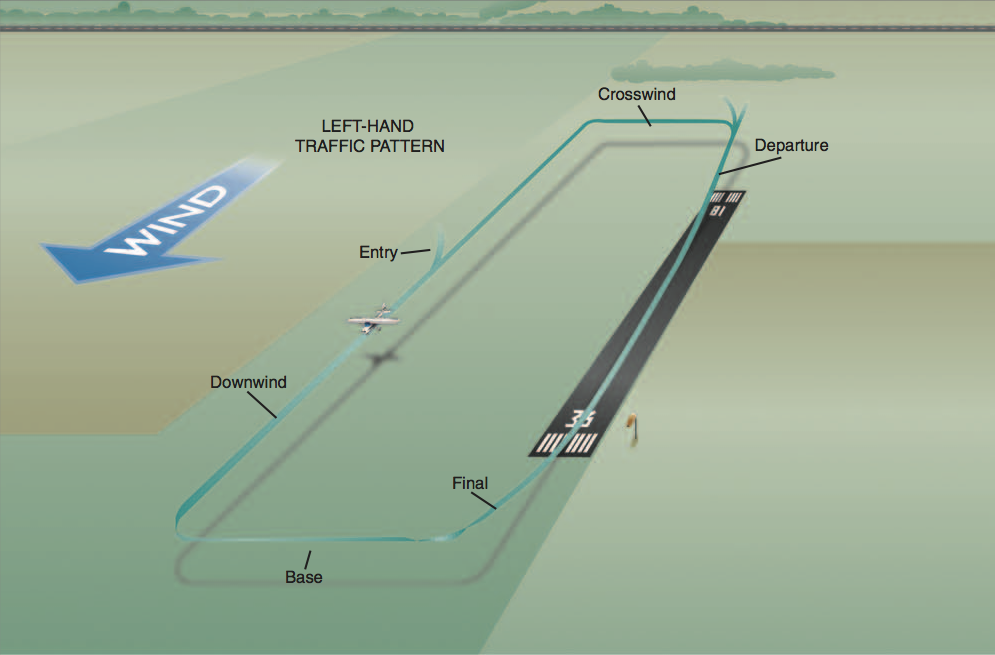

The cross-country flight was spectacular. All the more so because I didn’t think I’d get to fly due to the weather: There was a cloud layer (“ceiling”) around 4,000 feet along much of the route, well below the 5,000 foot minimum required by my flight school for cross-country flights. Also, the surface winds were gusting to 16 knots at KBED and 18 knots at KGON, both above the 15-knot limit that my instructor chose for my original solo endorsement. But my instructor waived both limits for the flight, citing his comfort level with how well I’ve been flying lately, and off I went at 3,000 feet.

It felt as though everything went right:

- My navigation was great. I chose to navigate primarily using VOR navigation, with dead reckoning as backup (following along on my aviation chart and looking for outside ground references to verify my position and course) and GPS as backup to the backup. In the past my VOR navigation has been shaky, but this time it was rock solid — thanks to my instructor’s advice to set up the navigation radios before I even taxied the airplane, instead of hurriedly trying to dial them in when I need them. My route was KBED to the GDM (Gardner, MA) VOR, to the PUT (Putnam, CT) VOR, to a landing at KGON (Groton, CT), thence direct to a landing at KEWB (New Bedford, MA), and back to KBED.

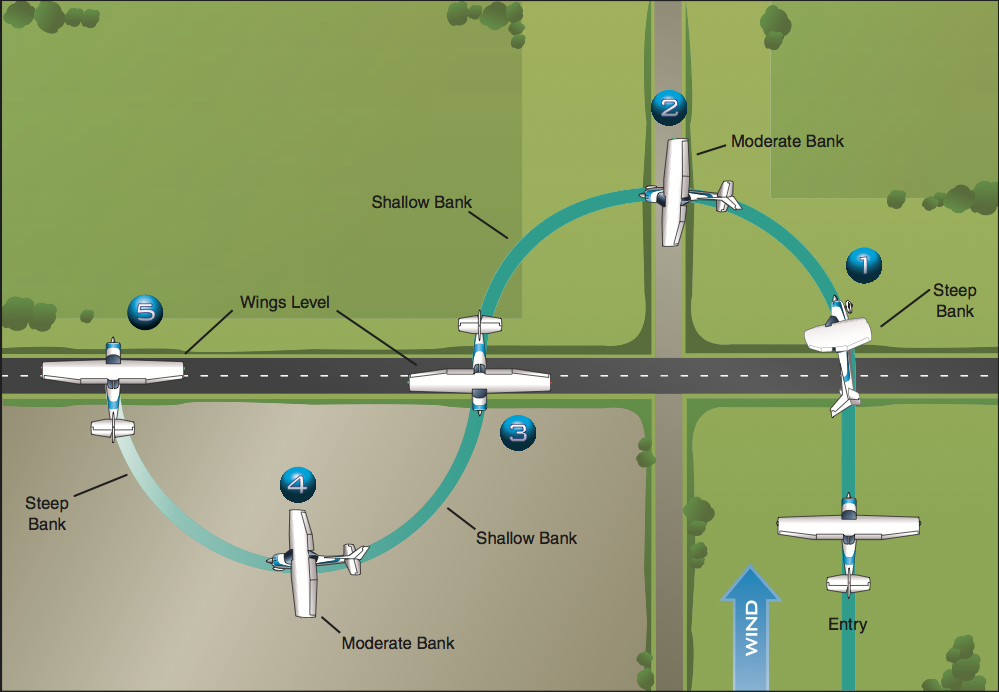

- My landings were great. Approaching KGON I twice asked the tower for a “wind check” to verify that the winds were still below the maximums to land; I was concerned both with the wind gusts and the “crosswind component” of the wind. (Pilots prefer the wind to blow steadily and directly down the runway. The winds at KGON were both gusty and at an angle to the runway; if the crosswind component of the gusts was greater than 8 knots then I was not authorized to land.) I was prepared throughout the landing to abort if the winds started gusting, but ended up with a landing so smooth it felt as though there were no wind whatsoever.

- The views were great. Here are some pictures:

Wow. Also:

and

Wow.

This weekend I passed my private pilot knowledge test, scoring 54 correct (90%) out of 60 questions. (A passing score is 70% or above.) The questions I missed were on the following topics:

- Hand-propping an airplane. Engines without electric starters require someone to go out and manually spin the propeller “old-school” to get the engine going. Since I don’t do any hand-propping I hadn’t even read the section of the Airplane Flying Handbook that explains the recommended procedure (“Contact!” etc.)

- Tri-color visual approach slope indicator (VASI). Does a tri-color VASI use a green, amber, or white light to indicate that you are on the correct glideslope? I answered white (I suppose I was thinking about a pulsating VASI) instead of the correct green. A tri-color VASI doesn’t even have a white light! I’m not sure there are any airports in the Northeast that still have a tri-color VASI in use, but if so I’d love to see one. EDIT: There are two nearby! Falmouth Airpark (5B6, Falmouth, MA) and Richmond Airport (08R, West Kingston, RI) both report tri-color VASIs in use.

- Characteristics of stable air masses. One of the neat things about learning to fly is that you learn a lot of arcane or obscure facts about weather systems, fog, etc., that generally are only going to be useful to you if you plan to fly through ugly weather. Apparently I didn’t learn enough arcane or obscure facts; I missed two weather-related questions.

- Emergency locator transmitter (ELT) maintenance. I said two years where the correct answer was one year.

- Dropping items from the airplane. It turns out it’s totally legit to drop things from an airplane! (I incorrectly answered that you are only allowed to do so in an emergency.) FAR 91.15: “No pilot in command of a civil aircraft may allow any object to be dropped from that aircraft in flight that creates a hazard to persons or property. However, this section does not prohibit the dropping of any object if reasonable precautions are taken to avoid injury or damage to persons or property.” During my post-exam review my instructor mentioned that he has returned car keys to his wife using this method.

So I’m inexorably closer to being done! I have a couple of in-school checkrides coming up with another instructor — the fifth instructor I will have flown with during my flight training — and if the weather cooperates I could take the final FAA oral test and checkride as early as October 10.